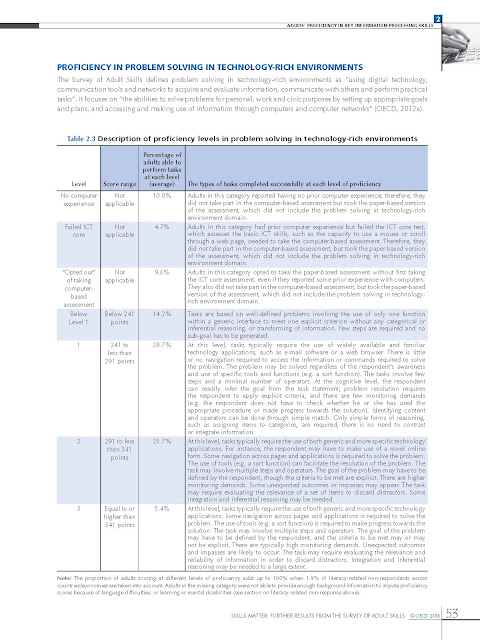

The OECD Skills Outlook Report (2016) states that many adults across all 33 surveyed nations – including New Zealand – “have no experience using computers, or extremely limited [digital competence] skills, or have low proficiency in problem solving in technology-rich environments”, with 25% having “no [experience] or only limited experience with computers or lacks confidence”, and that almost 50% of adults are “at or below Level 1” (see the table following) in digital competence. The report surveyed a range of adults and clustered them, detailing the skill level, as follows (p. 53):

Those with digital competence “tend to have better outcomes in the labour market than their less-proficient peers. They have somewhat greater chances of being employed and, if employed, of earning higher wages” (OECD, 2016, p. 26). They go on to say that “New Zealand stands out as the one [nation] whose adults use almost all information-processing skills the most frequently at work” (OECD, 2016, p. 116). For most roles – 90% - in New Zealand, digital competence above Level 3 is expected.

In my vocational opinion work I often encounter people whose computer skills are not yet at Level 1 (see image above). They are, effectively, digitally incompetent. The education sector in New Zealand has stopped delivering training to those who do not yet have digital competence - the tail of the population not yet IT savvy. This was once the domain of the Polytechnic sector, but, as the polytechs have to be run as businesses, and the computer training no longer brings in an appropriate level of income, the computer training was pushed online. There were three assumptions made here: firstly that learners will be digitally competent enough to get online in the first place to seek training without a guide; secondly, that they will have enough knowledge to be able to find out what they don't yet know - a training needs analysis - then find an appropriate course to fill the gap; and thirdly, that they will have the hardware, software, and connectivity hardware and expertise available so that they are able to access online courses.

Further, as a digitally incompetent adult, you may not be able to keyboard, may not read well, and think that a computer is a magic box which behaves incomprehensibly. Not having a teacher to be their "guide on the side" (King, 1993, p. 30) to build confidence and show the learner how to navigate problems provides a significant barrier to learning.

Those who are not yet digitally competent usually have complex reasons for having missed the development of these key skills. Their learning may have been complicated by being out of work, and therefore unable to pay someone to help them. This then becomes a vicious cycle by being limited in the work they can get because of their lack of computer skills. If they have been injured, they may not be able to return to the work they are able to do. Or their roles may have disappeared, and they are no longer able to compete in the workforce.

So how do those who are not yet digitally competent now become digitally competent? How do those who have fallen through the cracks find the resources to reach current expected standards? It is a difficult problem.

There are currently no easy answers.

Sam

References:

- Isograd (2020a). FAQ: What is the explanation of the TOSA score? https://www.isograd.com/EN/faq.php

- King, A. (1993). From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.1993.9926781

- OECD (2016). OECD Skills Studies: Skills matter, Further results from the survey of adult skills .http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en

- Rao, S. M., Harrington, D., & Parsons, M. W. (2000). Acquisition of keyboarding skills: An event-related fMRI study. NeuroImage, 11(5), S361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(00)91292-8

- Selwyn, N., Gorard, S., & Furlong, J. (2006). Adult Learning in the Digital Age: Information technology and the learning society. Routledge.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Thanks for your feedback. The elves will post it shortly.